F.

Gehr: Red Face {Roter Kopf}

Ferdinand Gehr (1896-1996, Saint City, Switzerland) began his career as a religious church painter. Gehr painted a simplified figurative fresco of a thunderstruck woman on the wall of the baptistery in Saint Martin, St. Gallen-Bruggen (1936). Many other religious commissions followed throughout his life, until well into his later years, with a now almost completely abstracted wall entitled Holy Spirit & Eternal Wisdom (1979).

The first decades of the 20th century were a long and intense period of spiritual self-discovery for Gehr. Over a period of almost 40 years, Ferdinand developed his personal style of reduced, simplified forms in bold, joyful colours arranged in dynamic compositions. He extended his work beyond the confines of the church walls, exploring its exterior, the natural world outside. Countless watercolours of floral arrangements en plein air followed in the 1950s, as did experiments with rudimentary coloured woodcuts. It was in these woodcuts that his contemporary Jean Arp found something wonderfully interesting, and I must say that I share his view (while looking at two flowers twisting around each other in the corner of the living room).

In the end, after a lifetime of exploratory development, Gehr fully articulated its own artistic language. This can be clearly seen in his woodcuts as well as in the larger, more elaborate tempera paintings that Gehr made as an old man in his 70s, in the 1970s.

Artificial Abstraction

This short detective story is not an art-historical analysis of the works of Ferdinand Gehr, but something a bit different.

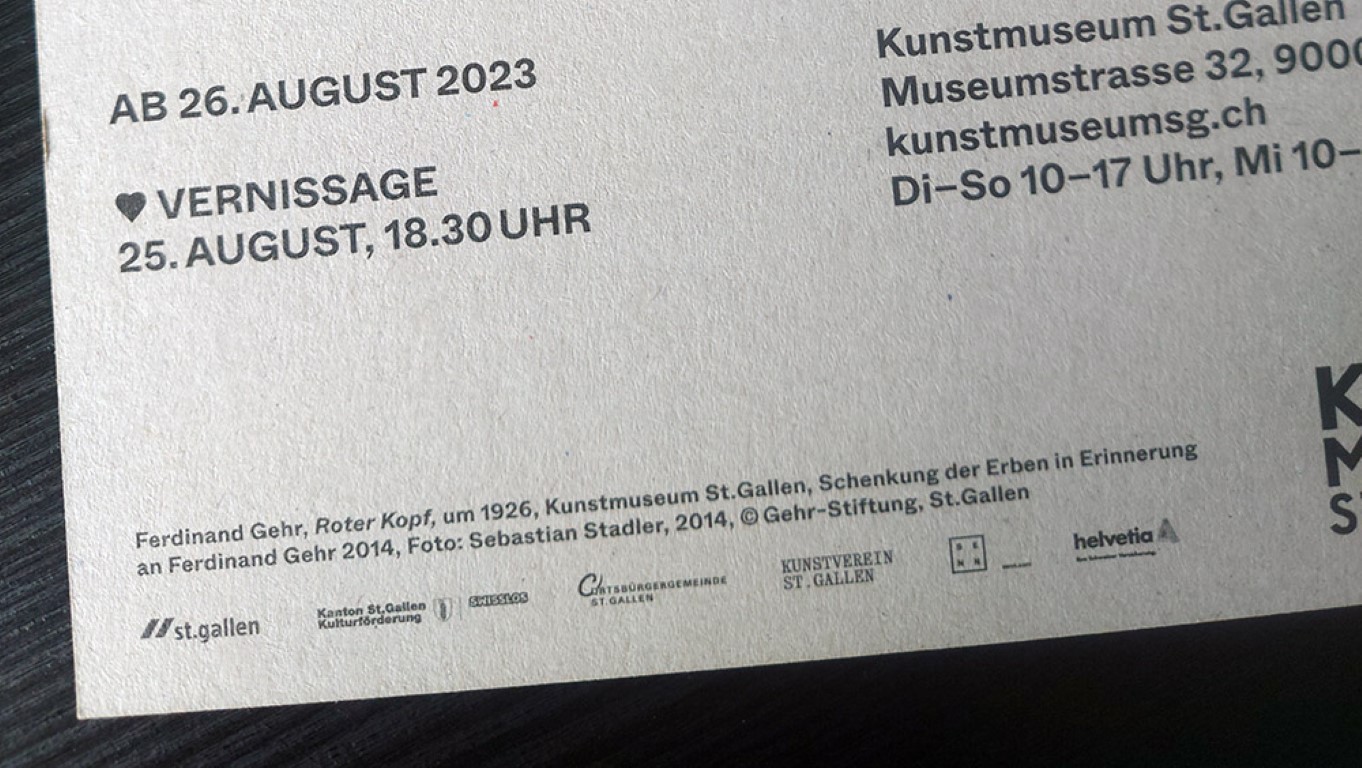

Two months ago, August 25., 2023, I went to the Kunstmuseum St. Gallen with a friend called M. Goldschmidt, an experienced art dealer based in the Zurich area. We were there to see 14. Juillet (1937) by John Konstantin Hansegger. To our surprise, Hansegger had been given a major upgrade: the painting had been moved upstairs to a central position in the permanent collection, after years of being kept in the dark privatised bunkers downstairs.

Hansegger's striped curtains were positioned directly opposite Gehr's painting, which was unofficially baptised: Red Face. As a true art dealer with Sammlungsfieber, M. Goldschmidt scanned the painting for signature and date.

M.: 54, Gehr, in the right-hand corner, with tiny handwriting. You can only see it from the right angle, look closely

We looked at the description on the wall; m... 1926. Okay, maybe there is a small unintentional mistake here? With sweaty hands I took the exhibition card out of my pocket, Red Face staring at me point blank. I turned the card over to read its description, In the right-hand corner, with a tiny font, again, Red Face, circa 1926.

I will report this to the Museum!

M.: But remember, don't expect to hear from them anytime soon. You know why. ;)

We relaxed for a while on a blown-up-business sofa by Pipilotti Rist and made our way down to the exit.

Back into the Future

In Abstract : Reality [Shadowplay] I discuss the relativity of dating works of art and how some artists, especially those famous throughout history, have dated their paintings back into the future in order to be ahead of the times and the competition. Rembrandt did it occasionally, Theo van Doesburg did it, and more recently Damian Hirst has done it again. In Hirst's case, however, the underlying contemporary reason is slightly different: it stems from his personal, absurd financial needs.

This practice is not limited to artists, some underworld art-historians or dealers also like to play around with dates (for the same contemporary reasons).

Red Face is undated, but if you want to write art history, you need numbers, facts! you need dates, to place this particularly red-faced painting in Ferdinand's presumably linear timeline. We should and must invent a date. Why not pick the most opportune date, preferably as early as possible? You can then place the painting in the manuscript of Ferdinand Gehr’s life’s work to create a wonderfully, compelling story. A story that unfolds in a single, pivotal moment: Roter Kopf.

“Ferdinand holds his candle, its soft glow casting shadows around him. He closes his eyes for 3 seconds, takes a slow, measured breath, and blows gently. Just then, a thunderstruck echoes through the darkened sky, striking the bell tower of Saint Martin. The bell tolls loudly: DING!” - 1:54-55

Gehr & Gehr

After the museum, we visited the - soon to be hidden again - temporary exhibition at a local auction house in the centre of St. Gallen that specialises in Liner, Liner and Gehr. There was an amazing orange Gehr up for sale that day, I call it: light-bulb-face, or on further inspection by Goldschmidt: a close-up of a flower-seed-cut-out.

That's Gehr! I shouted without opening my mouth.

At the other end of the exhibition was another, smaller Gehr, in his own distinctively realistic style, vaguely reminiscent of a postcard, showing a field of Dutch tulips sprinkled with forget-me-nots. A special edition, because it was the only one, I had ever seen signed in gold.

Back at home, I was scrolling through Artprice's database, while browsing through some of his previous art exhibition catalogues. I stopped somewhere in the middle, looked her intensely in the eyes and muttered, 'Maria'. In the catalogue, a black and white cropped unsigned image, but also online at Artprice, 'Maria' & Child', one of his earliest works, dated 1926, with a sloppy signature and, fortunately, a large advertising banner diagonally crossing the composition.

Another, Magnificat (1925), reminds me of an early Cubist cut-out composition by Juan Gris, straight lines, but this one with very strong colours, this other on Artprice again, the same, strong colours but this one painted sloppy.

Look there, we found two more, Invaluable for sure, a depiction of a colourfully abstracted forest with purple trees (1984), as always strong signature colours. Artsale mentions it as well, the same work, I mean almost the same. I wonder why, I definitely would not buy this edition, neither would Goldschmidt when I asked him.

Many Gehrs

Gehr & Gehr...for some special reason in history he has been split in two. No one in the town of Saint City fully understood how it happened; not even Ferdinand himself. The first Ferdinand, a man known for his childishly simple church murals, now found himself shadowed by a silent companion — a nearly identical reflection casting an uncertain shadow on many of his painted walls.

Many Gehrs (2024), Marcel Moonen

At first, I thought I was dreaming, as he’d somehow entered one of his own paintings, where flowers often appeared in duplicity, embracing and separating under a luminous skies. Yet every time he tried to shake himself free, the other Ferdinands followed, mimicking his every step with eerie precision.

Many Gehrs.

It was as if he had become his own unfinished portrait.

Ⓜ Author: Marcel Moonen, all rights reserved, F. Gehr: Red Face {Roter Kopf}, 10.10.24 [EDUCATIONAL PURPOSE ONLY] Triple-A Society, M. Production