Eladio Dieste, and the curvature of a brick

*Iglesia de Atlántida Cristo Obrero y Nuestra Señora de Lourdes (1958) - Eladio Dieste elected Unesco World Heritage.

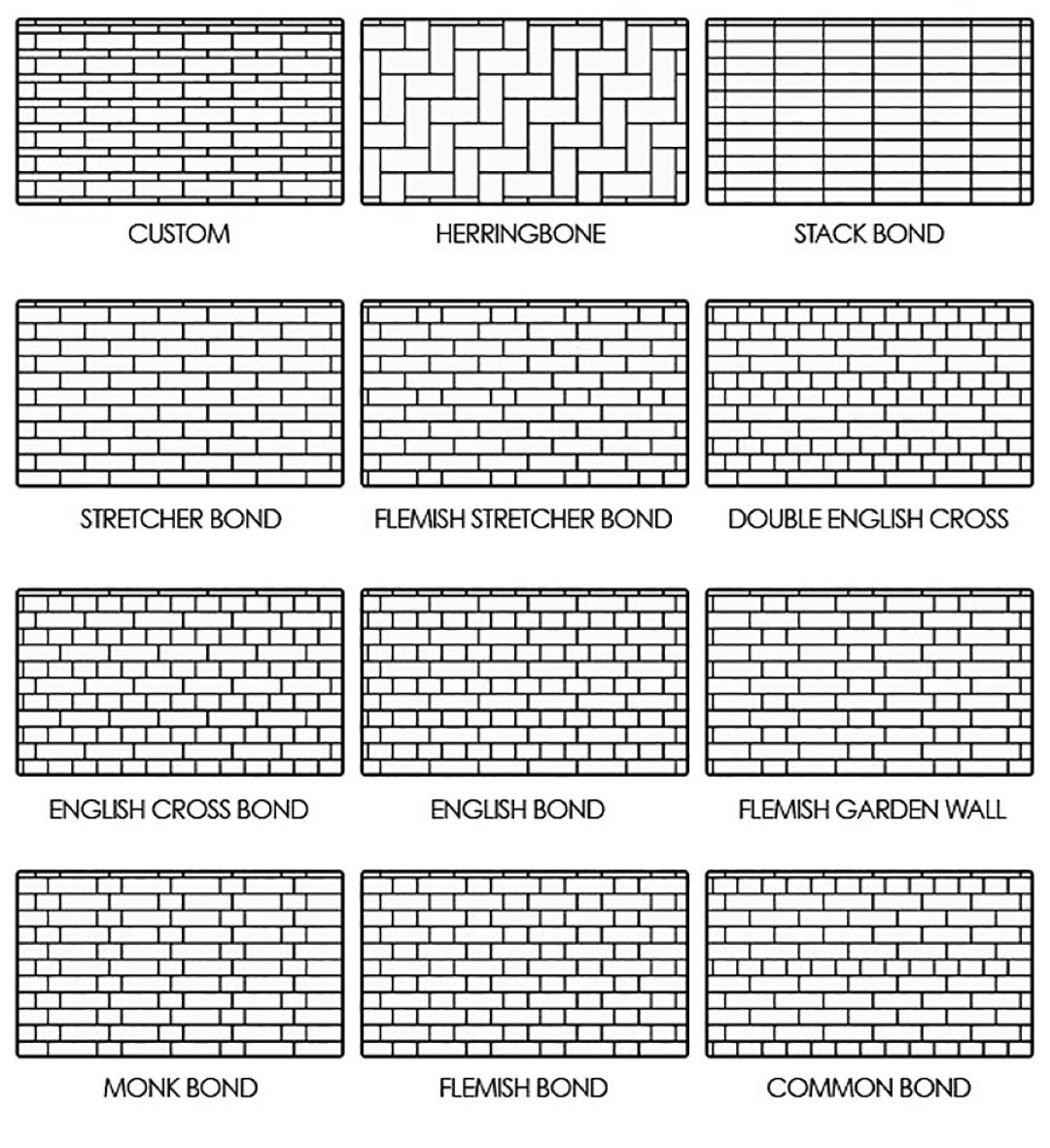

Being born and raised in the Netherlands I’m all familiar with brick buildings. As it is the traditional building material in the country, I have seen bricks in great variety and bonding.

The old Dutch towns and walls are mostly constructed in the conventional brownish brickwork. In modern buildings we observe the shiny surface of hard glazed baked brick, in blue, yellow or pink. With wide, narrow, or even open joints if you’d like.

During my studies in architecture, I learnt about the different approaches of using brick as a construction material. I read Berlage’s (Hendrik, Petrus 1856–1934) ideas about the apparent sincere use of materials, mostly brickwork in that case.

I took a closer look at the expressive, sea-like use of brick by the architects and master craftsmen of the Amsterdam School (1910–1930).

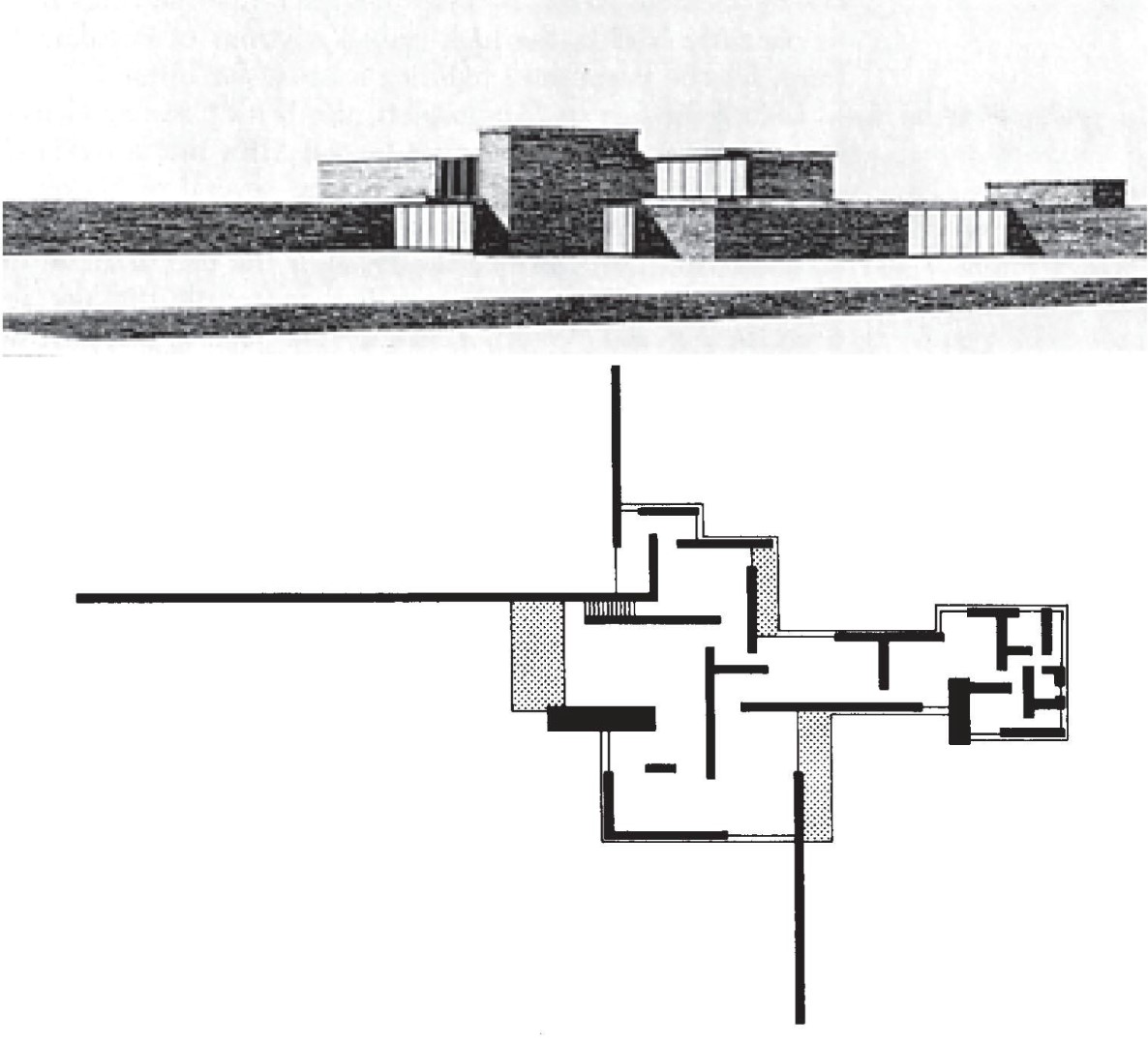

I saw drawings of Mies (1886–1969) in his Brick country house (1923–1924), with the idea to completely fill up meter thick walls with brick. Ought to love those bricks, though.

Meanwhile, while looking out the window(2000–2010), new-traditional constructions in the Netherlands were being erected; according to the supervision of the one (and only), Luxembourgish architect Rob Krier (1938), and company.

Just kidding, he is the {shadow}brother of the more famous younger Luxembourgish architect Léon Krier (1946). Léon made some great drawings, while not building anything in a period of 20 years. He re-discovered, with his sketches, some neglected ancient rules about the size, scale and proportion of towns and cities. Nothing new though, just things we moderns have forgotten during time. His brother Rob helped put these ideas to practice. Constructing new neighborhoods, that “at first sight” appear to be old towns, mainly in brickwork.

Funny enough, bricks were not stacked on top of each-other during construction, but instead prefabricated in factories and later placed as instant ready-made wallpapers around concrete shelves.

Wallpapering brickwork

We started out with the brick as a construction material, but we ended up with the brick as fancy wallpaper. A triple-layered system: the construction-material; prefab concrete or cement blocks (1), insulation (2) and the covering with a brick panel (3). A way of building that is a bit more expensive than a double-layered compact plaster-work system; (1) prefab concrete or cement blocks and (2) insulation directly covered with a thin layer of plaster. But they say it looks better.

Nowadays we have reached a level of extreme expertise in constructing brick-wallpaper, gluing brick to cantilevering parts of building, creating fully-closed-brick-coats (except the roof) all around, resulting in, oh so beautiful Mirage-Buildings.

.

For the last five years I have lived in Switzerland, a country with a different building tradition than the Netherlands; there are not so many brick buildings around here, most architects prefer the greyness of concrete instead.

I almost forgot all about those bricks, till I travelled one day to the other side of the world. In South-America (Uruguay) I found a type of brick I had never seen before, this is not any regular brick, this is an extraordinary brick; a Hyperbrick.

Engineering Architecture; the minimalist approach

Eladio Dieste (1917–200) was an engineer who started out helping architects execute their constructions. He assisted Antoni Bonet in constructing a house at the coastline in Madonado, Uruguay.

Dieste would come up with a way to create a very thin, arched roof structure, but the architect Bonet didn’t like it so thin. He insisted on covering the structure; the roof would appear visually thicker, all painted in a nice shiny white.

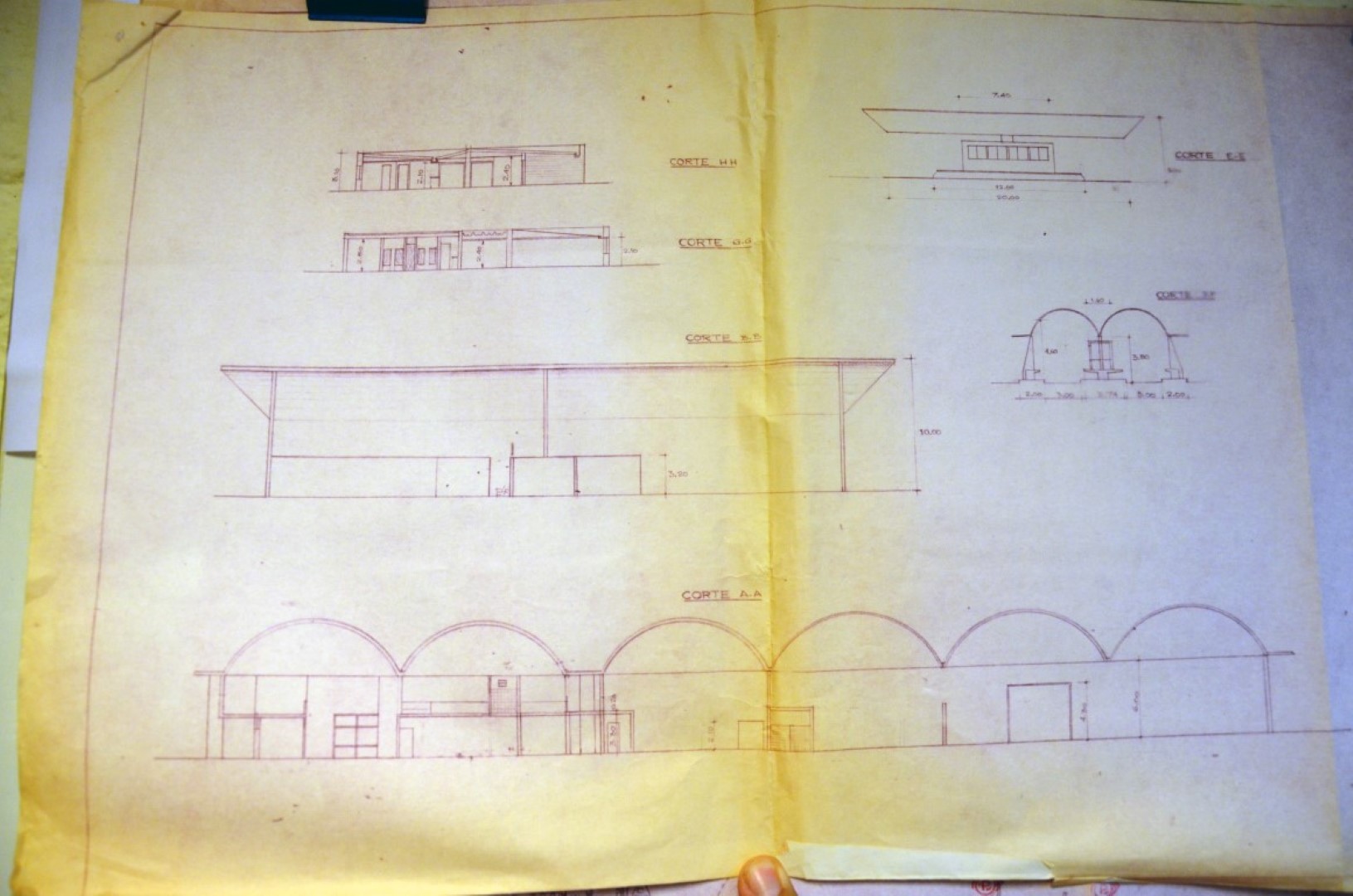

At a certain point, Eladio Dieste started acquiring his own assignments. No villas or museums for this guy, but mostly industrial types of buildings; factories, sport halls, bus-stops, that sort of thing. Demanding big open spaces, resulting in large roof spans. (Most of these buildings are in the small town of Salto, Uruguay.) All the structures had to be constructed with a minimal budget.

The perfect opportunity arrived for Eladio Dieste to bring his Thin-Gaussian-Vault-Brick-Roof-Idea into realization.

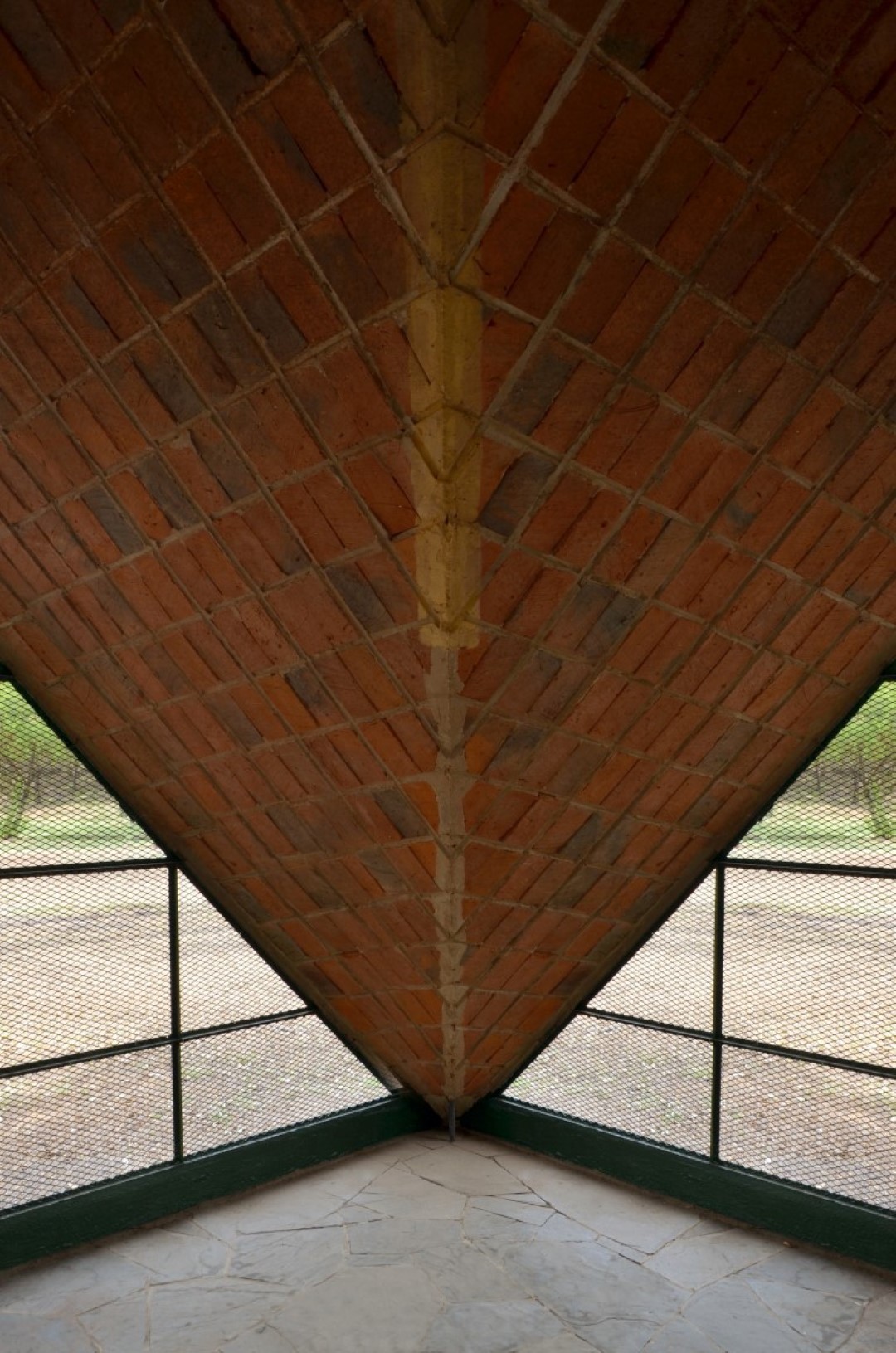

With the vault and brick in mind he would do something completely unusual. “Dieste created thin-shell structures for roofs in single-layered brick; stiffness and strength are derived from its double curvature (a catenary arch that resists buckling failure.)” [1] These forms were cheaper than reinforced concrete because it didn’t require ribs and beams.

Dieste’s buildings were incredibly economical in their use of materials; since labour of skilled craftsmen was cheap at that time, it was mostly a matter of material-costs. The roofs and walls were often only a single brick thick, achieving its strength and stability through curves.

While building his factory buildings, Dieste was commissioned to construct a couple of churches (one being an internal renewal of an existing old church). Dieste went all-in-to brick, with these projects. You may consider these churches an ode to the brick, to the inventive fusion of craftsmanship, engineering, art and architecture.

He also had the privilege to design a shopping center and his own house (more info here) in Montevideo (which is still for sale; if you are interested and like bricks, vaults, a sea view, candombe and have the money).

The shadow of Eladio

There has been extensive research on the structural behavior of his Gaussian brick vault, for example the book called; Eladio Dieste: Innovation in Structural Art by Stanford Anderson, and there are quite a few research papers found in the ETH, EPFL and other universities; but all from a technical-structural perspective. There has not been much written about Eladio’s role and position in the history of architecture.

Dieste, if mentioned, is often placed as the shadow of another American architect-engineer; Félix Candela (1910–1997), who made breakthrough innovation in the use of reinforced concrete. Félix Candela ‘s buildings have become a more familiar imprint into the collective minds of architects.

Something we, on this day, cannot say about the work of Eladio Dieste. His building still seems unusual, unearthly and for some even strange. Then again: Who ever thought bricks could fly?

You must be kidding, right?

While the mainstream architecture world is busy with the newest wallpaper {mirage-buildings}{for example Bernard Tschumi’s Tianjin Binhai Exploratorium, a science museum — wallpapering Dieste’s Montevideo shopping center}, Eladio Dieste guides towards a forgotten way of practicing architecture. He questioned the true nature of matter and structure; with considering an economical perspective: eventually coming up with surprisingly simple, extraordinarily innovative ideas.

Unfortunately, his oeuvre is quite neglected; many of his industrial buildings are in bad condition and severely damaged throughout the years; his churches and sport-complexes are nonetheless reasonably well preserved.

Door of Wisdom {Gas station} : The Gull

During my travels to Uruguay in 2017 I visited almost all the Eladio Dieste’s buildings in the country. Thanks to the help of friendly locals, I could even enter some of them. Hereby I show a selection of the pictures I took.

Functional Buildings

Churches

“The resistant virtues of the structure that we make depend on their form; it is through their form that they are stable and not because of an awkward accumulation of materials. There is nothing more noble and elegant from an intellectual viewpoint than this; resistance through form” — Eladio Dieste, The Engineer’s Contribution to Contemporary Architecture.

Eladio Dieste, and the curvature of a brick. Part of an ongoing research on the work of Eladio Dieste. Notes are linked into the text. [EDUCATIONAL PURPOSE ONLY]

Triple-A Society, M. Production© First published 10.2019